This model has been the saving grace behind all my software development projects and has saved countless hours of resolving merge conflicts.

I was first introduced to the gitflow model during my first group project, Big Balls Roll, by my group member Peter Crabbe. Thanks to the clear and basic structure it provides for a project, it made the daunting task of learning and using git a lot more manageable.

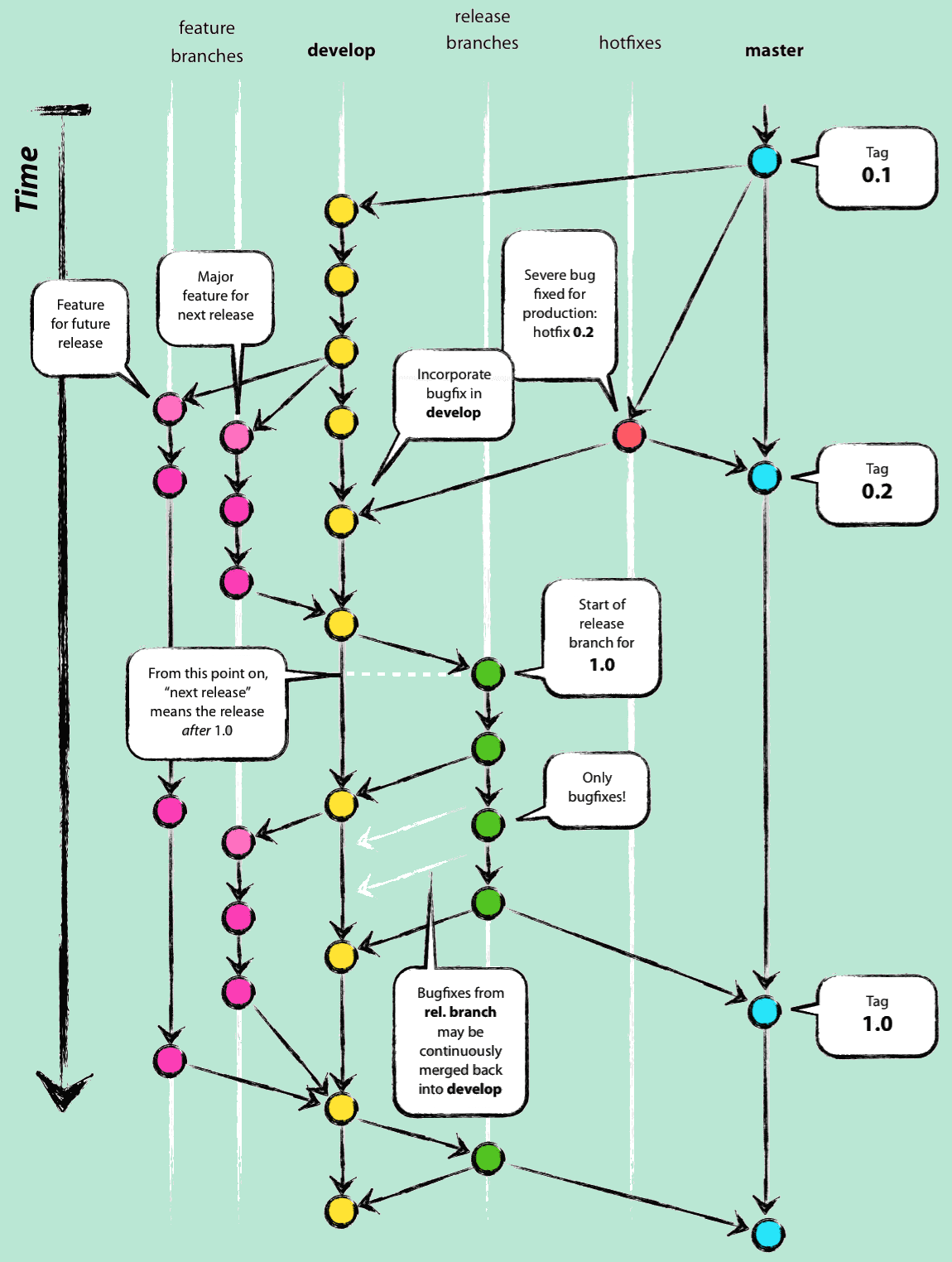

Vincent Driessen | A Successful Git Branching Model | Creative Commons BY-SA

The master and develop branches are the two branches whose lifespan is active throughout the entire project. The master branch is production-ready code, although it is pushed to once a significant milestone or requirement was achieved for my university-based projects. The develop branch is where all approved branches rejoin the larger codebase, and new feature branches are created. The development branch can quickly get hundreds of commits ahead of the master branch, so it is vital to plan milestones ahead of time and allocate sufficient testing so that the master branch can stay relatively up to date.

Feature branches are used to add new functionality to the software in an isolated branch independent of other feature branches. Several branches can be worked on simultaneously, with each adding code that should not affect any existing code in the project.

In addition to these main branches, several ‘fix’ branches are often created within projects I have worked on instead of having a separate release branch. This is primarily due to the nature of university projects where there is usually only one release, the final product. These fix branches are small and only fix one issue at a time to minimise challenges finding where code broke further into the project.

While this model may not be the most optimal, it has served very well for the scope of my past projects. It has provided a solid foundation from which me and others I have worked with could form a solid structure for our group projects and ensure that we were all on the same page with the branching process.

For a more detailed explanation, you can read the original article here: A Successful Git Branching Model